(Letzte Bearbeitung / last updated on 05/02/2025)

Zum Zeitpunkt dieses Interviews war Lila Williamson, geb. Lieselotte Koch, 88 Jahre alt. Das Originalvideo ist hier zu finden und wurde mir von ihren Kindern Leslie und Lance als Kopie zur Verfügung gestellt, als ich sie im Oktober 2024 in Chicago besuchte. Ich habe die Abschrift des Interviews aus dem Holocaust-Museum Florida leicht verbessert, mit Anmerkungen versehen und einige Bilder hinzugefügt.

Mein Name ist Marina Berkovich. Heute ist der 22. August 2012. Ich führe ein Interview mit Lila Williamson, einer Überlebenden des Holocaust. Dieses Interview wird im Auftrag des Holocaust Museum and Education Center of Southwest Florida für das Oral/Visual History Project geführt. Ziel dieses Interviews ist es, die Zeugnisse von Menschen in Südwest-Florida zu bewahren, die das Grauen des Holocausts persönlich erlebt und beobachtet haben, damit künftige Generationen wissen, was geschehen ist.

Wie ist Ihr Name?

Also, ich heiße heute Lila Williamson. In Wirklichkeit wurde ich als Lieselotte Koch geboren. Das ist mein Geburtsname.

Wann wurden Sie geboren?

Im Oktober 1923 in Mainz, Deutschland.

Was war das genaue Geburtsdatum?

Der 2. Oktober.

Und wie lange haben Sie dort gelebt?

Ich habe nie in Mainz gelebt. Meine Eltern lebten in Alzey, was nicht weit entfernt war. Aber das Krankenhaus war offensichtlich nicht gut genug für meinen Vater, also gingen sie nach Mainz ins Krankenhaus. Aber meine Eltern und meine Großeltern lebten in Alzey.

Wie lautete der Mädchenname Ihrer Mutter?

Guckenheimer, G-U-C-K-E-N-H-E-I-M-E-R.

Wie lautete ihr Vorname?

Erna, E-R-N-A.

Wo wurde sie geboren?

Im Mai 1902.

Und in welchem Land wurde sie geboren?

In Deutschland.

Erzählen Sie mir ein wenig über Ihre Mutter.

Ich kann mich nur sehr wenig an sie erinnern. Sie starb, als ich fünf Jahre alt war.

Wie hieß Ihr Vater?

Der Name meines Vaters ist Otto, O-T-T-O.

Wo wurde er geboren?

In Alzey.

Wissen Sie, in welchem Jahr er geboren wurde?

- Ich erinnere mich nicht mehr an seinen Geburtstag.

Welchen Beruf hat er ausgeübt?

Er war Handelsvertreter. Er war zusammen mit meinem Großvater im Geschäft. Sie hatten eine Mühle, in die die Leute ihren rohen Mais und Weizen brachten, und sie mahlten ihn und machten Mehl daraus. Ich habe gesehen, wie die Leute kamen und die Säcke mit dem Mehl hinaus trugen.

Hatten oder haben Sie noch weitere Geschwister?

Ich habe eine Schwester. Meine Schwester Ruth ist anderthalb Jahre jünger als ich, und sie lebt in Chicago.

Wie hießen die Eltern Ihres Vaters? Wo haben sie gelebt? Was haben sie gemacht?

Meine Oma hieß Thekla, T-H-E-K-L-A. Und ihr Mädchenname war Engel, E-N-G-E-L. Mein Großvater hieß Ludwig, L-U-D-W-I-G.

Und wie war ihr Nachname?

Koch.

Wo haben sie vor dem Zweiten Weltkrieg gelebt?

In Alzey. Sie hatten ein großes Haus mit einem Hof, und dahinter war ihr Geschäft, die Mühle. Und dahinter war ein Garten mit Gemüse und Bäumen.

Was wissen Sie noch über sie?

Sehr wenig, denn als meine Mutter starb, zogen meine Schwester und ich zu den anderen Großeltern, zu den Eltern meiner Mutter, die in Groß-Gerau lebten, weil sie dachten, sie könnten sich besser um uns kümmern. Aber wir haben auch die Koch-Großeltern besucht. Wir wurden sozusagen hin und her gereicht. Aber die meiste Zeit habe ich in Groß-Gerau gelebt, und ich bin dort zur Schule gegangen. Ich bin dort ins Gymnasium gegangen. Und das Gymnasium dauerte ungefähr bis zur zweiten oder dritten Klasse. Das nächste, woran ich mich wirklich erinnere, ist die Kristallnacht.

Wie haben die Eltern Ihrer Mutter gehießen?

Die Namen von den Eltern meiner Mutter? Guckenheimer.

Wie hieß Ihre Großmutter?

Settchen, S-E-T-T-C-H-E-N. Und mein Großvater hieß Adolf, A-D-O-L-F.

Was hat Ihr Großvater gemacht?

Nun, er hatte ein Holzlager. Ein großes Holzlager. Er verkaufte Holz und Kohle und fast alles, was mit Bauen zu tun hatte. Hier haben wir gewohnt [zeigt 3 Fotos]. Das ist das Haus, in dem wir wohnten:

Und das war ein Teil des Holzlagers:

ies war eine Art Wohnzimmer, und dies war das Schlafzimmer [zeigt auf Fenster im ersten Stock]:

Es ist ein sehr schönes Haus. Welche gesellschaftliche Stellung hatten Ihre Großeltern in dieser Stadt?

Oh, sie haben alles gemacht. Sie gehörten zur jüdischen Gemeinde. Wir hatten eine Synagogel. Und dorthin gingen wir in den Ferien. Und sie gingen am Samstagmorgen hin. Das war ein Ritual, da gingen sie hin. Die Nachbarn, die um sie herum wohnten, waren nicht alle jüdisch. Manche von ihnen waren jüdisch.

Hat Ihre Großmutter zu dieser Zeit noch gearbeitet?

Nein.

Hat Ihre Mutter gearbeitet?

Nein.

Wie war der Beruf Ihrer Mutter, den Sie mir genannt haben?

Keinen. Ich glaube, sie war Hausfrau und Mutter.

Wissen Sie noch, wie sie aussah?

Eigentlich nicht. Sehr wenig. Nein. Meine Großeltern, die aus Groß-Gerau, wir hatten Hilfe im Haus, und mein Großvater hatte sogar ein Auto. Wir hatten einen Mann, der uns gefahren hat. Manchmal hat er mich auch zur Schule gefahren.

Hatten sie eine sonstige Hilfe, eine Haushaltshilfe? Hatten sie eine Köchin?

Ja, sie hatten eine Köchin. Die kam morgens und blieb und machte alles Mögliche. Sie hat viel gekocht. Auch meine Großmutter hat viel gekocht.

Die Helfer, die im Haus Ihrer Großeltern arbeiteten, waren die jüdisch?

Nein! Überhaupt nicht. Sie wohnten in der Stadt nebenan. Ich weiß nicht mehr, wie sie gekommen sind. Aber ich sah sie – wie war ihr Name? Gretchen! Ich habe sie gesehen, als ich 1991 oder 92 zurück nach Deutschland kam. Ich habe sie besucht.

Wer hat noch im Haus gearbeitet? Sie und Ihre Schwester waren sehr jung. Hatten Sie außer Ihren Großeltern noch jemanden, der sich um Sie kümmerte?

Ja, wir hatten ein Kinderfräulein, weil meine Großeltern meinten, sie seien zu alt, um sich mit uns Kindern abzugeben. Wir hatten sehr nette Kinderfräuleins. Ich habe sie auch später noch getroffen. Sie waren nicht viel älter als wir. Aber es waren nette jüdische Mädchen aus gutem Hause, die uns Manieren beibrachten.

Wie alt waren Sie, als sie Ihnen Manieren beibrachten? War das vor der Einschulung oder danach?

Nein. Sie waren immer da. Als ich zur Schule ging, halfen sie mir bei den Schularbeiten. Sie haben viele Dinge getan. Sie waren die rechte Hand meiner Großmutter.

Wie lange haben Sie in Groß-Gerau gelebt?

Bis zur Reichskristallnacht.1Das Ereignis, auf das sich Lila bezieht und das die Großeltern zwang, Groß-Gerau zu verlassen, war nicht die Reichskristallnacht, sondern der so genannte „Judenboykott“, der in der Nacht vom 31. März auf den 1. April von der SA in ganz Deutschland mit Angriffen auf jüdische Geschäfte eingeleitet wurde. Wie Lila später im Interview erläutern wird, waren die Guckenheimer Großeltern davon so stark betroffen, dass sie sich gezwungen sahen, ihr Familienunternehmen aufzugeben und nach Frankfurt zu ziehen, wo sie sich in der Anonymität der Großstadt und im Umfeld einer starken jüdischen Gemeinde mehr Sicherheit erhofften. Der Umzug von Groß-Gerau nach Frankfurt fand im September 1933 statt.

Welche Sprache sprachen Sie zu Hause?

Deutsch.

Haben Sie noch andere Sprachen gesprochen?

Nein, nein.

Haben Ihre Großeltern, die in die Synagoge gingen, Sie religiös erzogen?

Ja, auf jeden Fall.

Wie haben sie Sie erzogen? Haben sie Ihnen Unterricht gegeben? Haben sie Sie zum Unterricht in den Gottesdienst mitgenommen?

Ein Teil davon war das Programm der jüdischen Gemeinde. Wir gehörten dazu. Mein Großvater war ein „Macher“.

Und wo befand sich Ihre Schule?

Fünf, sechs Blocks von unserem Wohnort entfernt.

War das eine jüdische Schule oder eine staatliche Schule?

Nein. Eine öffentliche, lokale Schule.

Können Sie etwas über Ihre Schule erzählen? Was wissen Sie noch über Ihre frühe Schulzeit?

Ich würde heute sagen, es war eine einfache Grundschule. Wir haben lesen gelernt. Wir lernten zu schreiben. Wir lernten zu spielen. Die Schule war sehr offen. Die Fenster waren immer offen, um frische Luft zu bekommen. Und es waren nicht viele Kinder in meiner Klasse. Es war ein ganz normales Gymnasium.

Was fällt Ihnen noch zu Groß-Gerau ein?

Groß-Gerau war eine schöne Stadt. Die Leute bauten auf den Feldern Spargel an, vor allem weißen Spargel. Das war ihre Spezialität, und sie hatten Lagerhäuser und Konservenfabriken, das war ein großes Geschäft. Woran kann ich mich noch erinnern? Wir hatten viel Wald um uns herum. Dort sind wir dann spazieren gegangen und haben Pilze gesammelt.

Wer waren Ihre Spielkameraden? Können Sie sich noch an jemanden erinnern?

Ich hatte damals wirklich keine Spielkameraden. Wir blieben immer in der Nähe des Hauses. Die Kinder auf der anderen Seite des Weges waren in unserem Alter, sie waren die Kinder eines Arztes und eigentlich die Enkelkinder eines Arztes. Manchmal haben wir mit ihnen Ball gespielt. Keine große Sache.

Hatten Ihre Großeltern viele Freunde?

Ja, sie hatten viele Freunde aus der Gemeinde, und ich erinnere mich an ein Pessach-Abendessen mit diesen und jenen Freunden, die alle nach Frankfurt in ein großes Hotel fuhren, wo sie ein Sederfest für die Leute abhielten, die kommen wollten.

Traurige Anmerkung: In einem Jahr – ich weiß nicht, wie alt ich war, fünf, sechs, sieben. Frau Gottschalk starb kurz vor dem Seder, und das hat dem Ganzen einen Dämpfer verpasst. Aber das Sederfest ging weiter und wir aßen. An diesem Abend fuhren wir zurück nach Groß-Gerau.

Wie alt waren Sie damals, was denken Sie?

Sechs, sieben Jahre oder so ungefähr.

Und wie alt waren Sie, als Sie Groß-Gerau verließen?

Als ich Groß-Gerau verließ, ging ich in die dritte Klasse in Frankfurt. War ich acht, neun, zehn?

Wie ging es weiter? Warum haben Sie Groß-Gerau verlassen?

Wegen der Kristallnacht.2In der Nacht vom 9. auf den 10. November 1938, der so genannten „Kristallnacht“, wurden Lilas Vater Otto und ihr Großvater Ludwig Koch in Alzey verhaftet. Mehr als 30.000 jüdische Männer in Deutschland wurden in die Konzentrationslager nach Dachau und Buchenwald deportiert. Zu diesem Zeitpunkt hatten Lilas Großeltern Guckenheimer bereits Groß-Gerau verlassen und lebten seit über fünf Jahren in Frankfurt. Das Ereignis, auf das sich Lila hier bezieht und das ihre Großeltern veranlasst hatte, nach Frankfurt zu ziehen, war nicht die „Kristallnacht“, sondern bereits der nationalsozialistische Aufruf zum Boykott jüdischer Geschäfte, der von nationalsozialistischen Schergen in der Nacht vom 31. März auf den 1. April in ganz Deutschland mit Anschlägen auf jüdische Geschäfte initiiert wurde. Die Nazis warfen Ziegelsteine in die Schlafzimmerfenster und einer davon traf meine Großmutter am Kopf. Wir sollten ins Badezimmer gehen, das zugemauert war, aber auch dort schlugen die Steine ein. Irgendwie ist das alles sehr verschwommen. Ich weiß nicht, wie wir von Groß-Gerau nach Frankfurt gekommen sind, wo wir dann eine Wohnung hatten. Wir lebten da in einer Wohnung und ich bin dort zur Schule gegangen.

An was können Sie sich noch erinnern von diesem Tag? Wie lange hat das Ganze gedauert?

Es war eine Aktion, die die ganze Nacht dauerte. Von einigen der Leute, die die Ziegelsteine geworfen haben, erfuhren wir erst Jahre später durch den Arzt, dem Arzt des Großvaters, wer sie waren. Es handelte sich um Leute, die zu den Kunden meines Großvaters gehörten.

Sie waren offensichtlich Deutsche.

Deutsche, ja.

Als die Großmutter am Kopf getroffen wurde, was ist da passiert?

Irgendwann kam der Arzt vorbei. Das war viel später, in der Nacht. Wir haben gewartet, bis die Steinschläge irgendwie zu Ende waren. Wir saßen einfach da, und der Arzt kam rüber und verband meine Großmutter. Aber kein Krankenhaus – nichts dergleichen.

Und warum nicht?

Ich weiß es nicht.

Woran können Sie sich noch erinnern, nachdem Sie so lange gewartet hatten und der Arzt kam? Hatten Sie Angst?

Sicher, sicher hatten wir Angst, ein Stockwerk tiefer wohnten noch der Bruder meines Großvaters und seine Frau.3Es handelt sich um Adolf Guckenheimers Bruder Ludwig, seine Frau Rosa und ihre beiden Töchter Else und Luzie, der mit seiner Familie im Parterre des Hauses der Gebrüder Guckenheimer wohnte. Beide Brüder verkauften das Geschäft und ihr Haus nach den Angriffen. Adolf und seine Frau zogen im Herbst 1933 mit ihren Enkeltöchtern nach Frankfurt, während Ludwig beschloss, mit seiner Familie nach Wiesbaden zu ziehen. Sie waren nicht verletzt, wurden nicht getroffen oder dergleichen. Man hat die Ziegelsteine einfach in den zweiten Stock geworfen. Über uns wohnte unser Hausmeister, der auch unser Chauffeur war, und wer weiß, was er sonst noch gemacht hat. Wir haben ihn in der ganzen Nacht nicht gesehen, ich weiß also nicht, ob er mit diesen Nazis unter einer Decke steckte oder nicht. Wir wissen es nicht. Ich weiß es nicht.

Woher wussten Sie, dass es Nazis waren?

Ich vermute, der Arzt von gegenüber hat es uns später erzählt. Nun, ich weiß nicht, inwieweit er mit ihnen verbunden war. Ich nehme an, ein wenig, denn seine Patienten waren Einheimische.

Und was geschah nach der Kristallnacht?

Ich weiß nicht mehr, was nach dieser Nacht geschah, bis wir nach Frankfurt kamen. Aber ich erinnere mich, dass ich plötzlich in einer Wohnung mit unseren Möbeln lebte. Gretchen, unser Dienstmädchen, und ihr Mann waren sehr damit beschäftigt, uns nach Frankfurt zu bringen. Die Möbel kamen dorthin. Viele Jahre später, als ich Gretchen in ihrer Wohnung besuchte, sah ich einige der Möbel, die meinen Großeltern gehört hatten.

War sie mit Ihnen nach Frankfurt gezogen?

Nein, sie lebte in einer kleinen Stadt in der Nähe. [[Mörfelden?]] Wie genau sie gependelt ist, weiß ich nicht. Es gab einen Zug und es gab einen Bus, mit dem sie kam. Und ich erinnere mich, dass sie, wenn sie nach Frankfurt kam, immer etwas in ihrer Tasche hatte, sei es ein Huhn oder Eier oder Kohl oder sonst etwas, was sie an diesem Tag mitbrachte.

Was wissen Sie noch von der Frankfurter Wohnung und Ihrem Leben in Frankfurt im Allgemeinen? In was für einem Viertel haben Sie gelebt?

Sehr nobel, sehr schön. Wir wohnten in der Hammanstraße, direkt neben einem Park.4Im September 1936 zogen Adolf und Settchen Guckenheimer in eine Mietwohnung in der Hammanstraße 4, etwa einen Kilometer vom Philanthropin entfernt. In der Hammanstraße wohnten damals vor allem wohlhabende Juden. Die Straße grenzte an einen kleinen Stadtpark, der damals Eysseneckpark hieß und nach dem Krieg in Holzhausenpark umbenannt worden ist. Nach dem Umzug aus Groß-Gerau wohnte die Familie Guckenheimer zunächst in einer Mietwohnung in der Scheffelstraße, die sich in unmittelbarer Nähe des Philanthropins befand. Ich ging in das Philanthropin, in eine jüdische Gemeindeschule, und mein Lehrer war Rabbiner Neuhauser – mit einem Stock.

Wie meinen Sie das?

Er hatte immer einen Stock dabei, und wenn du etwas nicht richtig gemacht hast, hat er dir auf die Finger geschlagen. (lacht)

Was hat er unterrichtet?

Meistens Hebräisch, und Geschichte. Wir hatten andere Lehrer für Englisch und einen anderen für Mathe. An den Kunstlehrer erinnere ich mich nicht mehr, aber es war eine sehr gute Schule, eine Privatschule.

Ging Ihre Schwester auch auf diese Schule?

Nein. Der Lehrplan war ziemlich steif und sie war dem nicht gewachsen. Sie ging auf eine nette kleine Mädchenschule.5Lilas Schwester Ruth besuchte von September 1933 bis Frühjahr 1936 ebenfalls das Philanthropin. Es gibt ein Klassenfoto aus 1936 mit ihr. Dann wechselte sie ins Dr. Heinemann’sche Mädchenpensionat im Frankfurter Westend in der Mendelsonstraße, auf dem zuvor auch ihre Mutter und Großmutter Settchen Schülerinnen waren (siehe Interview mit Ruth Veit, geb. Koch).

Können Sie mir sagen, wie ein normaler Tag aussah? Sie sind in die Schule gegangen, und was passierte, nachdem Sie aus der Schule kamen?

Ich bin mit einigen meiner jüdischen Freunde zur Schule gegangen, die auch auf diese Schule waren. Einige von ihnen leben immer noch in New York und Umgebung. Als ich im Jahr 1999 in New York war, habe ich sie gesehen. Ich habe sechs von ihnen gesehen. Sie sind alle noch da. Schule war Schule, und wir gingen morgens dorthin. Wir kamen zum Mittagessen nach Hause. Wir hatten, welches Fach auch immer, und wir gingen nach Hause. Die Nachmittage haben wir meistens damit verbracht, dass das Kinderfräulein mit uns in den Park gegangen ist, entweder mit einem Ball oder mit dem Fahrrad. Für mich war diese Zeit aber ziemlich normal. So ist das bei Kindern, wenn sie zur Schule gehen.

Erinnern Sie sich daran, welche Art von Spielen Sie damals gespielt haben?

Die meisten Spiele, die wir gespielt haben, fanden auf dem Schulhof statt – auf dem großen Hof. Es gab so eine Art Volleyballspiel. Die Mädchen und die Jungen wurden getrennt. Und natürlich haben wir immer zu den Jungs geschaut. Wir hatten eine Turnhalle, in der wir aber auch das hatten, was man heute Feld- und Leichtathletikspiele nennt. Sport wurde groß geschrieben.

Was hat Ihr Großvater gemacht, nachdem Sie nach Frankfurt gezogen waren?

Nichts. Von 1933 bis 1935 betrieb Adolf Guckenheimer in Frankfurt in der Keplerstraße 7a ein kleines Kohlengeschäft, bis die jüdische Bevölkerung von jeglicher Teilnahme am Wirtschaftsleben ausgeschlossen wurde.

Was geschah mit seiner Holzhandlung?

Ich habe keine Ahnung.

Und Ihre Großmutter, hat sie zu Hause gekocht?

Ja, das war ihre Aufgabe. Aber viel mehr haben sie nicht gemacht. Sie sind noch gereist. Ihr Lieblingsort war der Schwarzwald. Ich weiß, dass ich einmal mit ihnen gereist bin, und wir waren in der Schweiz und in Holland. Auch damals.

In welchem Jahr war das?

1933 und ’34. Die Kristallnacht war 1933.

Hat Sie Ihr Vater in Frankfurt besucht?

Nein, nein. Diese Großeltern haben nicht mit jenen Großeltern gesprochen. Sie haben einfach nicht geredet. Sie hatten nur uns als gemeinsamen Nenner. Und wenn wir in die Schulferien kamen, besuchten wir die anderen Großeltern in Alzey. Sie wohnten noch dort, aber nicht mehr in dem großen Haus. Das ganze Gebäude, die gesamte Mühle, wurde von jemandem übernommen. Ich weiß nicht, ob es Nazis waren. Es waren nichtjüdische Leute, die dann die Mühle betrieben, denn die Stadt und vor allem die katholische Kirche waren davon abhängig. Die katholische Kirche wurde mit einem Teil des Mehls versorgt, das meine Großmutter an sie schickte. Das haben sie beibehalten, das weiß ich, denn als ich zurückkehrte, ging ich in die katholische Kirche und besuchte eine der Nonnen, die sich um meine Großmutter gekümmert hatte. Sie hat uns einmal besucht. Meine Großmutter hatte Beinbeschwerden, und diese Nonne kam und verband die Beine meiner Großmutter, aber sie ging immer mit einem kleinen Sack Mehl nach Hause. So ging das.

Zurück zu Ihrem Leben in Frankfurt und Ihrer Zeit in der Schule: Haben Sie bemerkt, wie sich die Verhältnisse zu ändern begannen?

Ja. Sie begannen sich zu verändern, aber ich lebte sehr behütet zwischen meinen Großeltern und dem Kinderfräulein und dem Klassenlehrer, den Leuten in der Schule. Wir haben sehr wenig mitbekommen. Es gab viele Dinge, die wir nicht mehr unternommen haben. Ich ging früher in einen Tanzkurs, den eine nichtjüdische Dame leitete. Plötzlich gingen wir nicht mehr hin. Sie wollte uns nicht als Schüler, sie wollte nicht, dass wir in ihr Studio kommen, sie war nicht bereit, jüdische Kinder zu unterrichten.

Hat sie Ihnen das direkt gesagt?

Nein. Ich weiß nicht. Ich vermute, dass meine Großmutter zu mir sagte: „Du hast keine Tanzstunden mehr.“ Ich glaube nicht, dass sie wirklich darüber gesprochen haben, wieso oder wieso nicht. Aber heute weiß ich Bescheid. Jahre später wusste ich den Grund.

Was hat sich sonst noch verändert?

Das war eines dieser Dinge. Am Samstagnachmittag gingen wir in ein Restaurant. Das war das Übliche. Man ging dorthin und trank „Kaffee und Kuchen“. Unsere Freunde waren da und ihre Kinder. Plötzlich gingen wir nicht mehr dorthin, weil jemand dort war, der nicht wollte, dass wir kommen. Ich kannte die Gründe nicht – wirklich nicht. Das waren alles so Sachen, die man uns Kindern vorenthalten hat. Man hat nicht mit den Kindern gesprochen, man hat den Kindern nicht alles erzählt. Was die Kinder nicht wissen sollten, wurde nicht besprochen. Ich hatte keine Ahnung, was Geld ist, bis ich fast zehn Jahre alt war.

Warum eigentlich nicht?

Ich brauchte keins. Jemand anderes kümmerte sich für mich darum. Plötzlich wurde ich erwachsen, und dann musste ich es wissen.

Was kauften Sie mit dem Geld, wenn Sie welches hatten?

Keine Ahnung. Kindersachen, Bleistifte. Ich erinnere mich, dass ich Bleistifte gekauft habe, ja.

Wie lange sind Sie in die Schule gegangen?

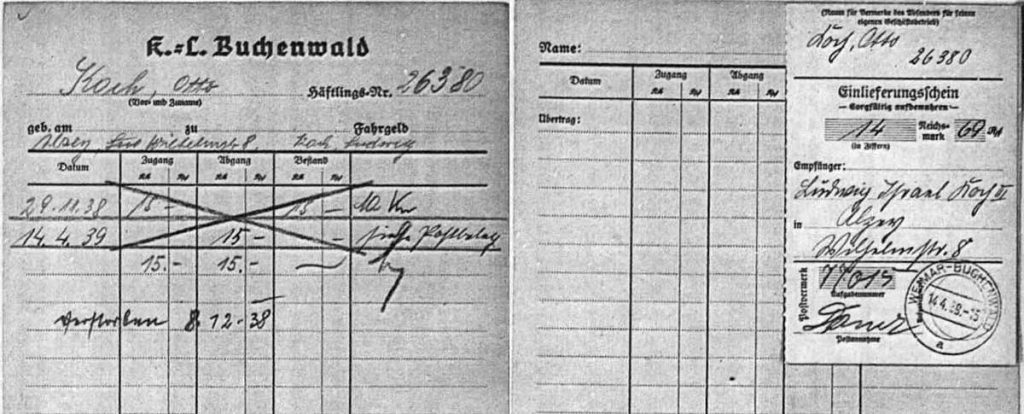

Wie lange ich in der Schule war? Bis 1939 oder 40. Bis alles offensichtlich wurde. Oh, zu dieser Zeit, 1939, lebte mein Vater noch in Alzey, und er war einer der allerersten, die von den Nazis ins Konzentrationslager abgeholt wurden.6Otto Koch wurde während der „Reichskristallnacht“ am 9.11.1938 verhaftet und nach Buchenwald deportiert. Er starb dort am 2. Dezember 1938. Seine Asche wurde an seine Eltern in Alzey geschickt. Lieselottes Schwester Ruth beschreibt in ihrem Interview von 2011 viele Details der Verhaftung ihres Vaters.

In welchem Jahr war das?

1939.

Wissen Sie, in welches Konzentrationslager?

Nein. Nein.

Was war sein Schicksal? Was geschah mit ihm? Ist er dort gestorben?

Vier Wochen später bekamen wir eine Nachricht, dass sie die Asche nach Hause schicken. Kein Kommentar. Nicht wie, warum, wann. Er starb und sie schickten die Asche nach Hause.

Haben Sie jemals mit seinen Eltern darüber gesprochen?

Klar, wir waren dort. Es gab eine Trauerfeier für ihn. Für die Asche. Die Familie meines Großvaters hatte ein Familiengrab, in dem einige der Kochs begraben waren, und dort wurde auch seine Asche beigesetzt.

Wie alt war er zu diesem Zeitpunkt ungefähr?

Er war knapp vierzig. 1898 – also 1939.

Wussten Sie zu diesem Zeitpunkt, was ein Konzentrationslager ist?

No, absolutely not.

Did anybody from your family understand?

No, no. It was talked about very thinly in school. None of the other kids’ parents had gone. Frankfurt was a big town, and I didn’t hear who went. A lot of the kids at school immigrated at that time with their parents around 1938 and 39.

And where they immigrate to?

Who knows. Some went to South America. Some of them went to Canada, and a lot of them went to New York.

When you were at school at that time and people were emigrating, were there any people that didn’t come to school? They were just disappearing and nobody knew what was happening to them?

Yeah. They just disappeared. They were gone.

And did anybody talk to the children about that?

Kids were gone with their parents.

But in school, did anybody talk to the children about it?

I don’t really know.

So how were you explaining that at that point in time?

At home they were talking about it, that we couldn’t stay there much longer and that we ought to go maybe to Holland where we had other relatives. The Jewish organizations in Frankfurt were busy saving the children. My sister, who was under a certain age – I don’t know, was it under thirteen – she could be adopted by a family in England. So off she went to Coventry. And I was with a group called HIAS and they were the ones who organized the Kindertransports. Somehow I got onto that and went to England.

Was it the Women’s group in these organizations? How did you learn about this Kindertransport?

It’s a local group that my grandfather I’m sure supported.

Were your grandparents looking for a way to place you?

Yes. They had to find safe places for us.

Why didn’t they go?

My grandfather couldn’t leave his money. That was a big thing at home. My grandmother wanted to go and go to Holland and he said, “No, we’ve got it good here. We stay here.” That I remember.

And by that time – other than the events of the Kristallnacht – was he mistreated in any way or did he believe that Germany was all beautiful?

Yeah, that Hitler will go away! He came, he did his thing, and he’ll go away. I’ll be safe here with my money. That was his philosophy. There was a lot more to it, but that was it. Yeah.

So they were discussing the safe ways for children to be sent away on their own, on your own?

Yes.

They were discussing it in front of you?

Yes. My father was gone and dead already when they sent us. Can you stop a minute? [Short break]

One of the trips, one of the vacation trips, I was sent on to Holland. My mother and my other cousins are a generation off, because we were much younger. So I was close to the cousin in Holland. And I visited her later on when she lived in Switzerland.7The person in mention is Meta Hochstädter (1903-1985), the daughter of Lila’s great-uncle Karl Hochstädter (1876-1943), who is the brother of Settchen Guckenheimer. And that’s when she told me that my grandmother had made a dress for me and sewed some of her jewelry in there. And that’s how I went to Holland. My cousin in Holland then promptly took the dress apart and found the jewelry. Here’s one piece (shows jewelry), but that’s all. But that’s what they did. Very material-minded.

So, as they were planning for you to leave, were your servants still working for your family?

By that time they had left. They just came when nobody was looking. And again, Gretchen would bring something, something to eat.

Were you not getting enough food to eat at that time?

I don’t know. All I can tell you is that we always ate good.

So do you remember how you were getting ready for your trip abroad?

My grandmother packed a little suitcase for me, and I don’t remember really what was in it. But when I got to England, I got packages from her with clothes and especially underwear. I should never do with dirty underwear. So I had clean underwear. And those packages came and they sent little goodies. Things she baked. And she still wrote to me in 19, what was it, ’39 and ’40.

Do you remember what date you left Germany?

Really not.

Do you remember how you left Germany?

I said goodbye to my grandparents and some lady came and took me to the train. Then eventually – I don’t really remember of how I got to England But in a transport, part of it was by bus. Yeah.

Do you remember how you were dressed? What season of the year it was?

No. Clothes, a skirt and a blouse, that was the uniform. Yeah.

Did you know what you would be doing in England?

Yes, I was supposed to live with a family that had a son about my age, and we were supposed to go to their Temple school together. When I got there, the mother of this boy looked at me and she said, “You two can’t live in the same house.” That was too tempting. By that time we were sixteen. So they shoved me off to their son who had a wife and a baby – not too far away. I learned to do things I never knew they existed. I learned how to lay a fire. I learned how to eat smelly fish [laughs] – some of these things. Take care of this little boy. Not exactly physically, but to watch him, and to push him in some kind of a carriage. But in the morning, I had to get up and lay the fire and make the coffee. I never knew how to do that!

When you arrived to England, were you alone or did you arrive there with other children as well?

I went to Temple school for a while, but they decided that wasn’t for me. They needed me to take care of their child, so that was the end of my school. And that family lasted just so long. They were ultra-orthodox people. You know, we went to Temple the whole bit.

Do you remember their name?

Their name was Adler, A-D-L-E-R. And I don’t even remember the child’s name. They were lovely people, but I didn’t suit them. So then I was shoved off to another family who had teenage girls. They were 11 and 12, and I could learn English from them. They went to public school. They were not ultra-orthodox. They were – they weren’t reformed, no – conservative. Temple still on Saturday morning. Of course we walked to Temple, you know, because you didn’t drive. I stayed with them until somehow this HIAS organization who is nationwide, international, found my cousin, aunt, whatever you want to call her. She’s a distant cousin to my grandmother Guckenheimer, whose maiden name was Hochstädter. Herr name was Hochstädter too. She was here and she wrote out this affidavit for me. I presumed that in years gone by, my grandfather had the insight to spread his money a little here and a little there. I know there was some in Switzerland. But she had some money to take care of me and my sister or whatever. But I should never be a burden to her.

When you were in England, do you remember the name of the town that you lived in?

Manchester. Manchester was a working town – dirty, coal mining, coal shipping. They were on water and there was lots of trade with the boats, with the coal being shipped. Mr. Adler was a lawyer. But the second family, I don’t even remember their name. They were horrible! He was just a salesman. I would say he made enough money to feed his family.

Did you know anything about the War at that point in time?

Of course we did. We knew what air raids, bombs, shelters are. When you heard the sirens, you hid in the shelters, either in your house or something close by. We happened to have a school close by where we ran to when we heard the sirens.

How often was that happening?

It happened. I don’t know. But in the meantime, my sister lived in Coventry and Coventry was one of those towns that were completely bombed. And the family she lived with, they lost their house with rubble and bombs. She learned to shift for herself. The family went, I don’t know where the family went. But they didn’t take care of her either. She went to live in Leeds. She left Coventry and went to live in Leeds.

Were you in touch with her at that time?

Yes, somehow. We knew where we were. No intimate phone calls or postcards. But we knew it.

Were the people from HIAS or any other Jewish organizations helping you, coming to check on you or facilitating your communication with your sister somehow?

I don’t know if HIAS was involved; I don’t know. It was a miserable, miserable year in England. In 1941, I came here. That was through HIAS. They took the children that had affidavits in America and put them on a boat. The boat was a minesweeper. It took about ten days. There were six girls to a cabin. One of us was more sick than the next one because seas were rough. You had to dodge mines in the sea, but somehow we made it. We were taken care of. Not grand, but somehow we made it.

At that point in time, did you let your grandparents in Germany – did they know that you were going on to United States? Were they still in communication with you?

No, no. I lost communications with them early part of 1940 when the Guckenheimers went to one concentration camp and the Kochs went to another, and that was the end.8For Lila, the trauma of being a Holocaust survivor apparently blocked her memory of the end of her relationship with her grandparents for decades. Between 1940 and 1941, both the Guckenheimer grandparents and the Koch grandparents wrote her dozens of letters. For the Guckenheimr grandparents, the correspondence ended shortly before their deportation in November 1941. For the Koch grandparents, the correspondence ended at the same time when the USA entered the war. Many of the heartbreaking letters that Lila received have been preserved and can be read on this website.

Did you know that they were going to a concentration camp?

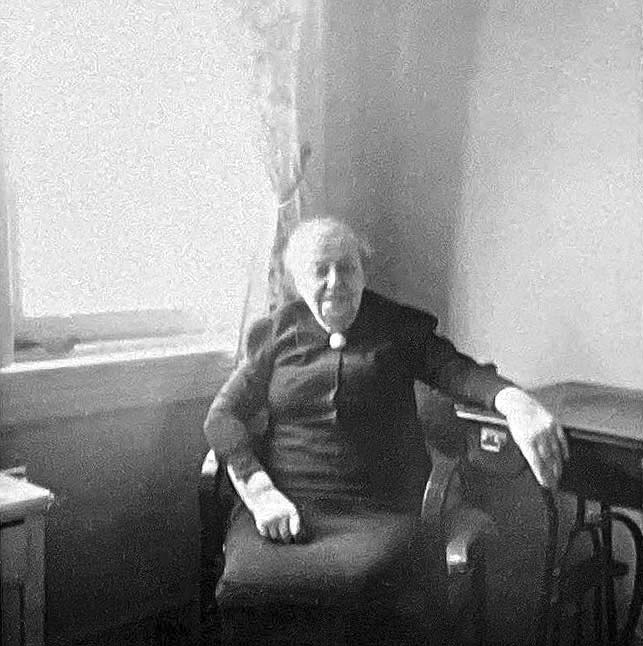

I presume through HIAS, I was told. Now, the Kochs, whatever happened to them, they stayed alive. Whatever my grandmother did, she did sewing for the Nazis, because that grandmother I brought here, and that’s how it came out. But my grandmother Koch was always the sickly one. She was the one who the nuns took care of for her legs. But she lived, and somehow they made it. My grandfather died as she would put it, “old age”. He was weak. He couldn’t handle some of the food and some of the doctors, whatever was available. But my grandfather had a sister in New York, and she helped my grandmother from there to New York, promising that I would get her.9The person in mention is Aunt Laura Liebmann, née Koch, Thekla’s sister-in-law, who emigrated to New York in 1938. This was strictly a stepping stone so that she could somehow recuperate, rest a little before she had to put it on me. After all, I was her granddaughter.

So in 1941, when you left England, do you remember the date that you left England?

Yes, sometime in April.

Do you remember the date that you arrived to the United States?

I got here.

Do you know what time of the day was it? Did you see the Statue of Liberty when you came on the minesweeper boat?

Of course I saw the Statue of Liberty!

Did you know about the Statue of Liberty?

Yes, yes. We were told on the ship to be sure to be on deck to see the Statue of Liberty. We were there, as sick as we were, but we were there! [Laughs]

And we waved to her, yeah. Another cousin on the Guckenheimer side, they immigrated, they were the daughters of the people on the first floor in Gross-Gerau. They immigrated something, I would say, 1937-8. They went to Italy early, early, early in the 1930s. They ran a hotel. Us kids, we would go there for vacations. But they came early and they went to New York. And she’s the one who met me at the ship, the boat.10The person in mention is Luzie Levi, née Guckenheimer (1906-1962). She is the daughter of Lila’s great-uncle Ludwig Guckenheimer (1873-1937), the brother of Adolf Guckenheimer. Lila lived with Luzi’s family in the Guckenheimer family home in Groß-Gerau until 1933. In 1937, Luzi and her father fled to San Remo in Italy. They apparently tried to run a hotel there. But Ludwig Guckenheimer died in San Remo on 27.6.1937. Luzie escaped with her husband Julius Levi from Italy to New York.

And do you remember your sentiment as you stepped onto the American soil?

I was so sick. The first thing she did was get me a bottle of seltzer water, as we called it “Bitzelwasser”. And she said, “You drink this and it will settle your stomach.”

And how long did you – ?

I stayed with her probably a couple of weeks. Her daughter my age, you know, we were there. And eventually I took a train to Chicago.

Stay in New York for a little bit. What do you remember about New York when you arrived?

First of all, I slept. And then there were quite a few cousins I never knew. My mother and my father were both only children, so I have no real cousins. But whatever I had, that’s who I saw. They were cousins.

Hold it a minute please. I need a drink. That’s a lot of talking. What else do you want to know?

Well, I would like to know what did you do in New York for these days that you were in New York and what happened after that?

In New York they showed me around. I walked myself silly over bridges and from this house to the next cousin’s house. I had a good time with my cousins my age. My aunts, as I called them, were good to me, trying to get me back on my feet because I guess I lost a lot of weight on this boat trip. Because we didn’t eat, we whoopsed.

Do you remember what neighborhood in New York you stayed in?

No. I don’t know.

And where did you go from New York? After you left New York, where did you go?

On a train to Chicago to my grandmother’s cousin who had money for me.

What was her name?

Her name was Tante Selig. She was born here and she never let me know that she had money for me, but she made sure that I knew enough English to get on the train and get a job.11Aunt Jenny Selig, née Hochstädter, who was born in Lampertheim in 1883, is the cousin of Lila’s grandmother Settchen Guckenheimer, née Hochstädter. Jenny emigrated to Chicago in 1911 with her husband Solly Spindel (1873-1924), her son Manfred (1909-1991) and her parents Moritz (1854-1927) and Sophie Hochstädter (1853-1945). In 1930 she married Sydney Hermann Selig (1873-1956). Her mother Sophie lived with her in the house at 7325 Constance Avenue in Chicago. Adolf Guckenheimer made contact with Jenny and Aunt Sophie at the beginning of 1938. They were to help get the children “out of ghostland” as quickly as possible and take Lila in. This was finally achieved in June 1940, when Lila received Jenny Selig’s affidavit for the USA in England and was able to leave for the USA. She lived in Aunt Selig’s household until her marriage to Leland Winter in 1943. I wasn’t here very long and I got a job at Carson Pirie Scott & Co. wrapping packages in the basement because my English wasn’t good enough to see the public.

What else do you remember about that time when you got to Chicago? Were your relatives kind to you? Were they worried about what happened to the rest of the family?

I don’t know. That was past. I was there already. Here today! And I met this boy from across the street that was going to the Chicago Law School, and he said, “You come along with me and I’ll get you a course where you can learn to talk English”.

What was this boy’s name?

This boy’s name was Leland Winter. I wound up marrying him. Yeah. [Laughs]

Did you learn enough English?

I learned enough English, yes.

What did you do after the university course?

When we got married, he was a law student. He graduated. He made the bar. While this was going on, I learned how to type and I typed his papers for him – whatever papers. We lived in Chicago, not far from his parents. His parents were very happy to see me because his mother comes from a little town not far from Gross-Gerau. His father came from Yugoslavia.

Do you remember which part of Chicago this was in?

Oh yeah, we lived on South Shore. We lived all right. We were poor. We lived with orange crates in the apartment, but we had enough.

Let’s talk about what you were doing in 19… What year were you married?

1942.

How long did your marriage last?

Thirty years. We had three kids and I divorced him when my youngest was 18 and we didn’t have to fight over the kids.

What are the names of your children?

My oldest was Laureen and she’s dead now. And then there’s Lance and then there’s Leslie. When these children were born, there were few other “Winter” children and they wanted us to name our children after this one and that one. We decided as long as his name was with an L, and my name was with and L, we named our children with L’s. We named them for my grandfather Ludwig and that settled it.

How many grandchildren do you have?

I have four.

What are their names and where are they? What do they do?

My youngest is Allison, and she’s leaving for college tomorrow; she’s going to Maine. Debates. Does it mean anything to you? My son has three children. There’s Elise, she’s 26. There’s Elena, she’s 24, and there’s Curtis who is 21. And I don’t have great-grandchildren. None of them are married.

Not yet?

No. I’m hoping.

Did you have a professional career? Did you have a work?

I worked wrapping packages. then I worked in a hat store. A very nice lady ran a hat store and I was the glorified errand girl. After that, I didn’t work for money for a couple of years. I did work for American Jewish Congress and the Drexel Home on the South Side. In the meantime, my grandmother was in New York and I brought her here and I had to find a place for her. She couldn’t live with me. I lived on the third floor and through the American Jewish Congress, I got her into this nice Drexel Home. but I had to work there volunteer, “Do this, honey”, you know. After a while, my husband got into other things and he wound up with the brick business. My husband was no businessman. He was a good lawyer, but no businessman. So I ran the business and I was lucky. I was female and it was strictly a man’s business. We bought the bricks as they came down from the buildings. There were crews that cleaned them up and stacked them and put them in railroad cars. It was up to me to ship them, to find customers to ship them to. The first customer we had was the Holiday Inn in Memphis.

What happened to your sister?

What happened to my sister? She met this nice boy in England and eventually I brought her here in early 1948. Her boyfriend came about the same time, but he had rich cousins in New York. Eventually he came here too and they got married and they settled in Chicago. They’re married 65 years now.

What is your sister’s name?

Ruth, yeah, and she’s a great-grandmother and she rubs it under my nose! [Laughs]

How, if any, your religious beliefs changed at all as a result of what happened to you?

My religious beliefs never changed. I was born Jewish, I was brought up Jewish, and even though I live in this very Christian retirement village, I’m still Jewish, and I let everybody know it.

Did your children follow your religious beliefs?

No. My daughter’s only child was Bar Mitzvah. She will be Jewish. My oldest granddaughter, my son’s oldest, will stay Jewish. The other two, they’ve got a Catholic mother.

You were married to your first husband for 30 years and you got divorced. Did you ever remarry again?

Yeah, I married Henry Williamson. He was the brother of the woman who taught my oldest daughter in Girl Scouts. Somehow I met him. They lived in Highland Park and they came to visit. He was happily married and I was married, and his wife got cancer and she died and I divorced my husband and somehow we got together. We were married 16 years.

What happened?

He had a heart attack on a cruise and died.

How long ago was this?

That was 1988.

Were you already in Florida at that time?

Oh, yes, yes!

You went to Germany, you said in 1990 or something like that?

I went to Germany in 1991 with a friend and it left me cold. What I saw was not what I remembered and what I remembered I wanted to remember and what I saw I could easily forget.

What do you mean?

Anti-Semitism is still there wherever you go. The person I traveled with also was military and we stayed at military bases, but we got out and we saw what goes on locally. You still saw swastikas in the bakery where we went and bought our lunch for the day. There was Anti-Semitism in certain areas. We were in Baden-Baden and they had some kind of demonstration. Definitely, Hitler Youths. I walked away.

Do you remember seeing some sort of demonstrations like that when you were a child?

I don’t remember that. That movement was very young then. I went back to Germany when the Germans invited my sister and me in 1988. This was a month after my husband died. But we went and we were treated royally, but the locals asked us to do things for their school. Actually it wasn’t the locals. It was the movement of the Germans that invited us. We should go to the schools and tell these kids that there was such a thing as the Holocaust, that my father was sent to a concentration camp. These kids just sat there with bare faces, couldn’t comprehend.

How old were these children?

These were seventh, eighth graders.

They were about as old as you were when you went to England. Do you remember the name of the organization in Germany that invited you and your sister?

No.

Which town was it? Was it in your hometown?

Where did we stay, we stayed in Frankfurt. Then we took a bus. We went to Gross-Gerau. That’s the city where we saw the kids in school and I saw some of the old buildings, you know, but I didn’t recognize any of the people there. That’s not when I went to see Gretchen. I went to see Gretchen with my friend that was in the military and we thought we could handle it. She told us when not to come because her son was home and he was strictly an SS boy. Now today, he’s my age.

He was SS during the war, during the Hitler time?

Yeah, but she asked us to come.

He was a member of SS?

Yeah.

Did she not want you to come because he was at home or something?

She wanted me to come. Not when her son was home. He was working. She was happy that I saw my grandmother’s credenza. Yeah. It was standing in her living room.

She was the one that used to be your grandparents’ maid?

Yeah.

And used to bring you food?

Yeah. She still lived in a little house where I remembered her to live, you know, all these years back.

Did you talk about your grandparents?

Vaguely. She told me that the last time that she saw them and I don’t remember when that was. I didn’t write it down. I was happy she saw them. And I got a hug and a kiss and we left. It was a matter of a half hour. Yeah.

Did her son during the war, did her son know that she came to visit your grandparents?

Who knows.

You don’t know that?

No.

That she seemed…, well obviously she was happy to see you, but did she seem emotional when you came?

No. No, cold, cold. I got a hug and a kiss, and that was about as far as she went. After all, she still felt like she was the maid. She was always the maid, even though my grandmother treated her royally. Even the maid in those days ate some of their meals with us. They didn’t eat in the kitchen. Kinderfräuleins for sure, but the maid, sometimes when it was a dinner that could be put on the table and she didn’t have to run and serve it. Right?

So the servants in your household, basically, on certain nights they were included in all of the family meals?

Yeah.

They should’ve felt like part of the family, you’re telling us?

Yeah.

Did you ever see the chauffeur that used to be your chauffeur?

No. No. He died some place along the way. Yeah. No, I never saw him.

But going back to the 1988 story that you were just saying right before, that there was an organization from – probably from Gross-Gerau – that invited you and your sister. How did they know to invite you? How did they find you?

My sister has a way of keeping in touch with everybody. I don’t know how she found them, but she said, “We’re invited – all expenses paid.” And they even invited my husband. And I said, “Sure. We’ll go.”

Have you ever met other people from Gross-Gerau whom you knew as a child that were Jewish?

No. My friends are from Frankfurt, and they’re the ones, in 1999 we were in New York and one of them made dinner and invited the other girls. I keep in touch with that one. Once – Rosh Hashanah, you know. And she tells me. It’s a phone call and we gossip for a half hour, and that’s it.

I’m just interested to find out if you know anything about the fate of these other people that were from Gross-Gerau whom were your grandparents friends from the Temple. You don’t know anything about anybody?

No. You have to remember my grandparents were a generation ahead of their parents, so there was very little contact. Their contact only was in Temple, you know. Yeah, they were older.

Is there anything that I’m leaving out that I haven’t asked you yet that you wanted to add about any of the experiences that you went through?

I have suppressed this for so many years that I wouldn’t talk about it when somebody asked me. I said, “Ah, forget it!” And even to my children, who know a little, not very much. I never really told them of how I grew up. They knew – my children met my grandmother when I brought her here. They went to visit her. Yeah.

Just once or have they kept up?

You try and get three kids together to visit their grandmother? Yeah. We did it. We brought her flowers, I would say, every couple of months.

She spoke German and your children,n did they speak German?

No. No. No.

So how were they able to communicate?

She said the right things in the right tones and she held their hands and she hugged them. And they knew that that was my grandmother. Yeah. I called her “Oma”, and today my grandchildren call me “Oma”.

What would you like your children, your grandchildren, everybody who is going to be your descendant, whom you’ve not met yet, and all of the other people that will ever watch this interview to know about how Holocaust affected you, or some sort of an outlook for the future that you would like to convey to them?

It was there. It existed. It’s not something that you can sweep under the carpet and forget. It was a time that existed, and it should be remembered for all those people who are not here anymore. How my children should know? Let them broadcast it that their mother was one of them, that she lived there and other people like me lived there, and somehow survived, and it should never ever happen again.

Thank you very much for letting us into your home and letting us interview you!

This has been Marina Berkowitz interviewing Lila Williamson about her experiences as a survivor of the Holocaust. This interview will be included as a valuable contribution to the oral visual history archives of the Holocaust Museum of Southwest Florida.

You did a good job! You did a wonderful job. Okay.

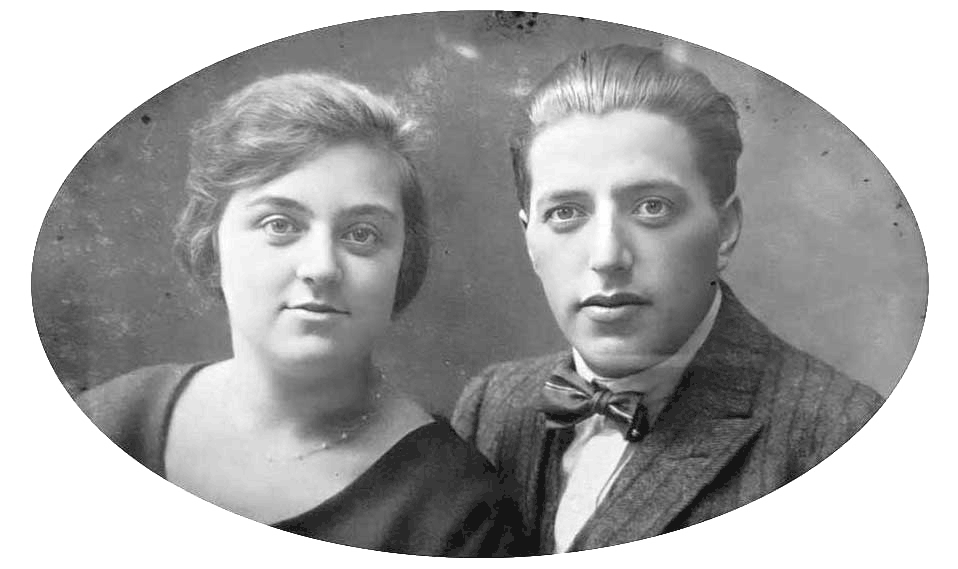

This is my calling card. My grandmother obviously had this made for me:

This is my mother and father and me on his automobile:

This is my parents all dressed up with furs and everything with some friends. I don’t know them:

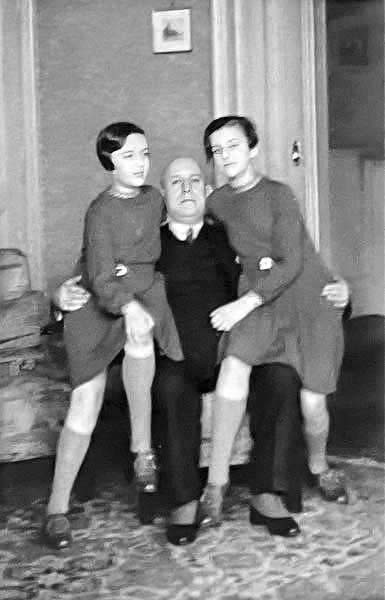

These are pictures of my sister and me:

This is the first day I went to school in Gross-Gerau, which was a to-do. You got a big like something filled with candy, a „Tüte“ (bag):

That is us as kids:

This is pretty close before we left:

I would say that is the last picture of my grandparents. You’ve had enough.

Anmerkungen / Notes

- 1Das Ereignis, auf das sich Lila bezieht und das die Großeltern zwang, Groß-Gerau zu verlassen, war nicht die Reichskristallnacht, sondern der so genannte „Judenboykott“, der in der Nacht vom 31. März auf den 1. April von der SA in ganz Deutschland mit Angriffen auf jüdische Geschäfte eingeleitet wurde. Wie Lila später im Interview erläutern wird, waren die Guckenheimer Großeltern davon so stark betroffen, dass sie sich gezwungen sahen, ihr Familienunternehmen aufzugeben und nach Frankfurt zu ziehen, wo sie sich in der Anonymität der Großstadt und im Umfeld einer starken jüdischen Gemeinde mehr Sicherheit erhofften. Der Umzug von Groß-Gerau nach Frankfurt fand im September 1933 statt.

- 2In der Nacht vom 9. auf den 10. November 1938, der so genannten „Kristallnacht“, wurden Lilas Vater Otto und ihr Großvater Ludwig Koch in Alzey verhaftet. Mehr als 30.000 jüdische Männer in Deutschland wurden in die Konzentrationslager nach Dachau und Buchenwald deportiert. Zu diesem Zeitpunkt hatten Lilas Großeltern Guckenheimer bereits Groß-Gerau verlassen und lebten seit über fünf Jahren in Frankfurt. Das Ereignis, auf das sich Lila hier bezieht und das ihre Großeltern veranlasst hatte, nach Frankfurt zu ziehen, war nicht die „Kristallnacht“, sondern bereits der nationalsozialistische Aufruf zum Boykott jüdischer Geschäfte, der von nationalsozialistischen Schergen in der Nacht vom 31. März auf den 1. April in ganz Deutschland mit Anschlägen auf jüdische Geschäfte initiiert wurde.

- 3Es handelt sich um Adolf Guckenheimers Bruder Ludwig, seine Frau Rosa und ihre beiden Töchter Else und Luzie, der mit seiner Familie im Parterre des Hauses der Gebrüder Guckenheimer wohnte. Beide Brüder verkauften das Geschäft und ihr Haus nach den Angriffen. Adolf und seine Frau zogen im Herbst 1933 mit ihren Enkeltöchtern nach Frankfurt, während Ludwig beschloss, mit seiner Familie nach Wiesbaden zu ziehen.

- 4Im September 1936 zogen Adolf und Settchen Guckenheimer in eine Mietwohnung in der Hammanstraße 4, etwa einen Kilometer vom Philanthropin entfernt. In der Hammanstraße wohnten damals vor allem wohlhabende Juden. Die Straße grenzte an einen kleinen Stadtpark, der damals Eysseneckpark hieß und nach dem Krieg in Holzhausenpark umbenannt worden ist. Nach dem Umzug aus Groß-Gerau wohnte die Familie Guckenheimer zunächst in einer Mietwohnung in der Scheffelstraße, die sich in unmittelbarer Nähe des Philanthropins befand.

- 5Lilas Schwester Ruth besuchte von September 1933 bis Frühjahr 1936 ebenfalls das Philanthropin. Es gibt ein Klassenfoto aus 1936 mit ihr. Dann wechselte sie ins Dr. Heinemann’sche Mädchenpensionat im Frankfurter Westend in der Mendelsonstraße, auf dem zuvor auch ihre Mutter und Großmutter Settchen Schülerinnen waren (siehe Interview mit Ruth Veit, geb. Koch).

- 6Otto Koch wurde während der „Reichskristallnacht“ am 9.11.1938 verhaftet und nach Buchenwald deportiert. Er starb dort am 2. Dezember 1938. Seine Asche wurde an seine Eltern in Alzey geschickt. Lieselottes Schwester Ruth beschreibt in ihrem Interview von 2011 viele Details der Verhaftung ihres Vaters.

- 7The person in mention is Meta Hochstädter (1903-1985), the daughter of Lila’s great-uncle Karl Hochstädter (1876-1943), who is the brother of Settchen Guckenheimer.

- 8For Lila, the trauma of being a Holocaust survivor apparently blocked her memory of the end of her relationship with her grandparents for decades. Between 1940 and 1941, both the Guckenheimer grandparents and the Koch grandparents wrote her dozens of letters. For the Guckenheimr grandparents, the correspondence ended shortly before their deportation in November 1941. For the Koch grandparents, the correspondence ended at the same time when the USA entered the war. Many of the heartbreaking letters that Lila received have been preserved and can be read on this website.

- 9The person in mention is Aunt Laura Liebmann, née Koch, Thekla’s sister-in-law, who emigrated to New York in 1938.

- 10The person in mention is Luzie Levi, née Guckenheimer (1906-1962). She is the daughter of Lila’s great-uncle Ludwig Guckenheimer (1873-1937), the brother of Adolf Guckenheimer. Lila lived with Luzi’s family in the Guckenheimer family home in Groß-Gerau until 1933. In 1937, Luzi and her father fled to San Remo in Italy. They apparently tried to run a hotel there. But Ludwig Guckenheimer died in San Remo on 27.6.1937. Luzie escaped with her husband Julius Levi from Italy to New York.

- 11Aunt Jenny Selig, née Hochstädter, who was born in Lampertheim in 1883, is the cousin of Lila’s grandmother Settchen Guckenheimer, née Hochstädter. Jenny emigrated to Chicago in 1911 with her husband Solly Spindel (1873-1924), her son Manfred (1909-1991) and her parents Moritz (1854-1927) and Sophie Hochstädter (1853-1945). In 1930 she married Sydney Hermann Selig (1873-1956). Her mother Sophie lived with her in the house at 7325 Constance Avenue in Chicago. Adolf Guckenheimer made contact with Jenny and Aunt Sophie at the beginning of 1938. They were to help get the children “out of ghostland” as quickly as possible and take Lila in. This was finally achieved in June 1940, when Lila received Jenny Selig’s affidavit for the USA in England and was able to leave for the USA. She lived in Aunt Selig’s household until her marriage to Leland Winter in 1943.