(Letzte Bearbeitung / last updated on 12/01/2025)

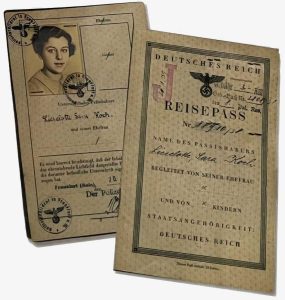

Lieselotte (*1923) und Ruth (*1925) wuchsen durch den frühen Tod ihrer Mutter Erna Koch, geb. Guckenheimer, ab 1926 bei ihren Großeltern in Groß-Gerau auf. Adolf und Settchen Guckenheimer übernahmen die Elternrolle für sie. In Frankfurt gelang es den Großeltern 1939, zunächst Ruth und etwas später Lieselotte mit einem Kindertransport nach England zu schicken. Der Abschied muss für die Kinder im Alter von 13 und 15 Jahren sehr schmerzhaft gewesen sein. Es sollte ein Abschied für immer werden. / Lieselotte (*1923) and Ruth (*1925) grew up with their grandparents in Groß-Gerau from 1926 due to the early death of their mother Erna Koch, née Guckenheimer. Adolf and Settchen Guckenheimer took over the parental role for them. In Frankfurt, the grandparents managed to send first Ruth and a little later Lieselotte to England on a Kindertransport in 1939. The parting must have been very painful for the children, who were 13 and 15 years old. It was to be a farewell forever.

Ersatzeltern

Nach dem Suizid der Mutter kümmerten sich „Oma Settchen“ und „Opa Adolf“ in Groß-Gerau um die Enkelkinder, die gerade einmal anderthalb und drei Jahre alt waren, und nahmen sie zu sich auf. Es entstand ein sehr inniges Verhältnis. So berichtete Lieselotte 2014 einer Journalistin in Florida von ihrer Überlebensgeschichte und ihrer beschützten frühen Kindheit bei den Großeltern. In dem Artikel „Secret Survivor“3Siehe Shell Point Life June 2014, Seite 40-41. wird deutlich, dass die Kinder sich bei den Großeltern in Groß-Gerau sehr behütet und wohl gefühlt haben. Über Jahre behielten sie weiter Kontakt zu ihrem Vater, der bei seinen Eltern in Alzey wohnen blieb. Dort besuchten die Kinder ihn gelegentlich sowie „Oma Thekla“ und „Opa Ludwig“. Damit blieben auch die Großeltern Koch für die Kinder über viele Jahre wichtige Bezugspersonen. Deren Bedeutung für das Aufwachsen der Kinder hob die Urenkelin Debra Hutter, geb. Veit (Jg. 1954), bei meinem Besuch der Familie in Chicago im Februar 2023 hervor. Der Vater sei dagegen für die Kinder „nicht hilfreich“ gewesen, sagte sie. In Groß-Gerau habe es bei den Großeltern Guckenheimer immer auch „nannies“ gegeben, die sich liebevoll um die Kinder kümmerten. „They lived a safe and comfortable life“, heißt es in „Secret Survivor“, bis zu dem Zeitpunkt, an dem die Großeltern Groß-Gerau verlassen und nach Frankfurt fliehen mussten.

Flucht nach Frankfurt

Am Beginn des nationalsozialistischen Boykotts jüdischer Geschäfte am 1. April 1933 war die Familie von SA-Mitgliedern angegriffen und überfallen worden, die Großmutter wurde verletzt. Adolf und Settchen Guckenheimer sahen sich gezwungen, ihre Existenz in Groß-Gerau aufzugeben und mit den Enkeltöchtern nach Frankfurt zu ziehen. Der verfolgungsbedingte Weggang aus Groß-Gerau fand im September 1933 statt. Die jüdischen Kinder waren nach Hitlers Machtergreifung immer mehr antisemitischen Anfeindungen und Bedrohungen in der Schule ausgesetzt. Sie wurden weitgehend aus Schulen, Parks, Schwimmbädern und Sportvereinen, aus öffentlichen Theatern und Jahrmärkten verbannt. Der Wechsel nach Frankfurt in eine Stadt mit einer starken jüdischen Gemeinde dürfte daher auch zum besseren Schutz der Kinder gedacht gewesen sein.

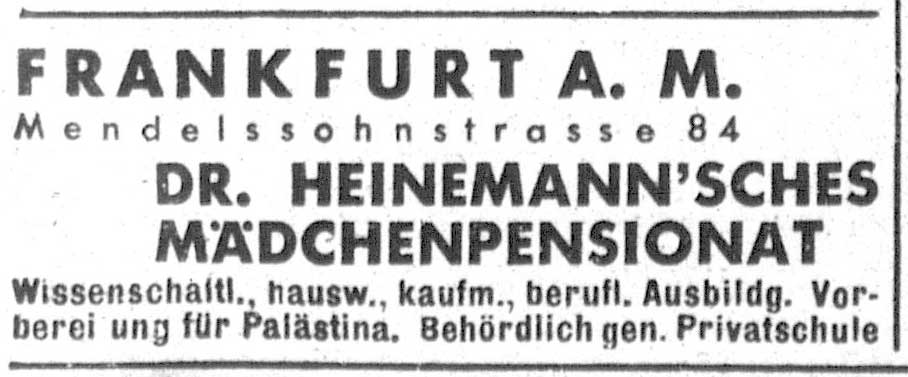

Philanthropin und Dr. Heinemann’sches Mädchenpensionat

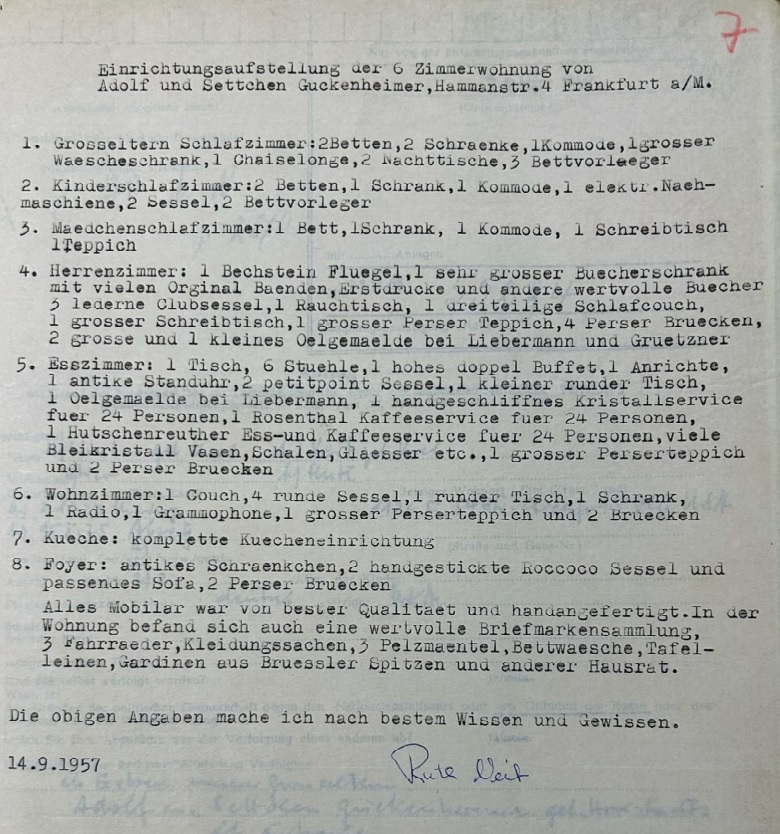

In Frankfurt besuchten die Enkeltöchter zunächst das Philanthropin, eine jüdische Schule, die sich in unmittelbarer Nachbarschaft zur neuen Mietwohnung der Großeltern in der Scheffelstraße 25 im Frankfurter Nordend befand. 1935 wechselten die Kinder in das „Dr. Heinemann’sche Mädchenpensionat“ in der Mendelssohnstraße 84 im Frankfurter Westend, das seine Schüler auf eine Ausreise nach Palästina vorbereiten sollte.4Diese Angaben zu den Schulbesuchen machte Ruth Veit 2006 bei ihrem Besuch in Frankfurt. Sie hatte mit ihrem Mann gemeinsam am Besuchsprogramm der Stadt Frankfurt teilgenommen. So berichtete mir Angelika Rieber, die das Besuchsprogramm für ehemalige jüdische Bewohner der Stadt seit 1980 leitet. Das Pensionat wurde als Internat und Externat geführt und war eine jüdische Privatschule mit „behördlich genehmigtem Unterricht“ bis zur „Obersekunda“. Ob die Kinder in dieser Zeit im Pensionat oder bei den Großeltern wohnten, daran kann sich Ruth Veit heute nicht mehr erinnern. Ihre Großeltern waren 1936 in die Hammanstraße 4 in eine neue Mietwohnung mit sechs Zimmern gezogen. Unter den Zimmern befand sich auch ein Kinderschlafzimmer mit „2 Betten, 1 Schrank, 1 Kommode, 1 elektr. Nähmaschine, 2 Sessel, 2 Bettvorleger“.5So heißt es in einem Gedächtnisprotokoll von Ruth aus dem Jahre 1957 (HHStAW Bestand 519/A Nr. FFM 6815/1, S. 7). Die Entfernung der neuen Wohnung zur Schule betrug 1,5 Kilometer und war damit für Kinder gut zu Fuß zu bewältigen. Insofern bestand auch die praktische Möglichkeit, dass die Kinder weiter bei den Großeltern schliefen und das Pensionat lediglich als Externat nutzen.

Die Novemberpogrome 1938

Lieselotte erinnerte sich an die traumatischen Erfahrungen der „Reichskristallnacht“. In dieser Nacht war Otto Koch, der Vater der Kinder, in Alzey inhaftiert worden und wurde wie 30.000 weitere jüdische Männer ins Konzentrationslager nach Buchwald verschleppt. Im Alter von 41 Jahren starb er dort wenige Wochen später am 8. Dezember 1938. Gleichzeitig vermischen sich in ihren Erinnerung die Ereignisse der „Reichskristallnacht“ mit dem bereits 1933 erfolgten Überfall der SA auf die Großeltern in ihrer Wohnung in Groß-Gerau, der zum Wegzug der Familie nach Frankfurt geführt hatte. Damals habe die Großmutter Verletzungen erlitten und die Familie musste im fensterlosen Bad der Wohnung einen Schutzraum aufsuchen.6Lila (Lieselotte) Williamsons Erinnerungen waren nach so vielen Jahren nicht immer sehr präzise in den Zeit- und Ortsangaben. So verlegt sie die Flucht der Familie von Groß-Gerau nach Frankfurt in die Zeit nach den Novemberpogromen 1938, dabei waren die Großeltern bereits 1933 nach Frankfurt geflüchtet. Die beiden dramatische Ereignisse liegen fünf Jahre auseinander.

Die Kindertransporte

Nach den verheerenden Novemberpogromen war die Weltöffentlichkeit über die brutale Verfolgung der Juden in Deutschland zwar alarmiert, aber lediglich die britische Regierung entschloss sich zu schnellem Handeln und vereinbarte mit einer Delegation britischer Juden und Quäker die Aufnahme einer unbegrenzten Anzahl von im Deutschen Reich bedrohten Kindern und Jugendlichen, die bis zum Alter von 17 Jahren ab sofort unbürokratisch einreisen durften. Ihre Eltern mussten jedoch in Deutschland zurückbleiben. Für die pauschale Duldung der privat organisierten Transporte nach England durch das NS-Regime hatten direkte Verhandlungen der legendären Geertruida Wijsmuller7Geertruida Wijsmuller war eine einflussreichen holländischen Jüdin und Bankiersfrau, die mit der Berlinerin Recha Freier zusammenarbeitete, der Gründerin der „Kinder- und Jugend-Alija“, einer Organisation, die ab 1933 versuchte, möglichst viele jüdische Kinder nach Palästina in Sicherheit zu bringen. mit Adolf Eichmann in Wien gesorgt, der damals die „Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung“ leitete. Auflage für die Ausreise war, dass die Kinder lediglich einen Koffer und nicht mehr als 10 Reichsmark mitnehmen durften und dass die Eltern sie nicht bis zum Bahnsteig begleiteten. Die Öffentlichkeit sollte von den dramatischen Abschiedsszenen nichts mitbekommen.

In Frankfurt wurde ab Januar 1939 die Kinderauswanderung von der jüdischen Wohlfahrtspflege der jüdischen Gemeinde für ganz Südwest-Deutschland organisiert. Die Kinder in den Zügen wurden von wenigen Erwachsenen aus den Hilfsorganisationen bis zur letzten Station vor der holländischen Grenze in Bad Bentheim begleitet. Nach schikanösen Kontrollen der Kinder und ihres Gepäcks an der Grenze durch die Gestapo ging die Weiterfahrt mit dem Zug bis Hoeck van Holland, von wo aus eine Fähre die Kinder über den Ärmelkanal nach Harwich brachte. Von dort wurden sie zunächst in Auffanglager gebracht, bis sich eine geeignete Pflegefamilie für sie fand. Der erste Kindertransport nach England startete am 1. Dezember 1938 von Berlin aus und brachte 196 jüdische Kinder nach London. Der Beginn des Zweiten Weltkriegs am 1. September 1939 war das offizielle Ende der Kindertransporte aus Deutschland. Bis zu diesem Zeitpunkt hatten über 10.000 Kinder aus Deutschland fliehen können.

Die Rettung von Ruth und Lieselotte vor den Nazis

Adolf und Settchen Guckenheimer hatten die aussichtslose Lage der Juden in Deutschland schon früh erkannt und sich kontinuierlich um eine Auswanderung bemüht. Durch die Initiative der Kindertransporte war die Ausreise ihrer Enkelinnen nun plötzlich möglich. Da beide Kinder durch den kürzlichen Tod ihres Vaters zu Waisen geworden waren, hatten sie gute Chancen, einen der begehrten Plätze für die Kindertransporte zu erhalten. Vor allem Waisenkinder, besonders wenn es sich um junge Mädchen handelte, wurden von den jüdischen Hilfsorganisationen an erster Stelle berücksichtigt. Auch fanden sie leichter einen Platz in einer Pflege- bzw. Adoptivfamilie in England. Der Artikel „Secret Survivor“ beschreibt die getrennte Ausreise der beiden Enkelkinder, ohne dabei genauer Zeitangaben zu machen:

“From Frankfort, the family managed to get Lila and Ruth transported to England with Kindertransport through a rescue organization known as HIAS. ’They tried to get the children out of Germany as fast as possible to keep us out of concentration camps,’ recalled Lila. Her sister went first, and was young enough to be adopted by a family in Coventry.”

Ruth kam im März 1939 vor ihrer älteren Schwester mit einem Kindertransport nach England, so erinnerte sie sich bei ihrem Besuch in Frankfurt 2006. In Coventry war sie von einer Familie gut aufgenommen worden. Zwei Briefe der Großeltern an sie in Coventry, die erhalten geblieben sind, sprechen von den neuen Adoptiveltern als „Onkel und Tante Josef“, denen Ruth offenbar „eine gute Stütze“ war und in deren Geschäft sich sich „nützlich zeigen“ konnte. Die Großmutter ermutigte sie in ihrem Schreiben vom 28. März 1940, nicht den Kopf hängen zu lassen: „Es wird auch wieder die Zeit kommen, wo wir alle wieder zusammen sein können. … Sei munter und vergnügt und es sind so viele Frankfurter Mädels dort und Ihr könnt Euch gegenseitig Eure Gedanken austauschen!“

Weniger gut war es dagegen Lieselotte ergangen, die erst Monate nach Ruths Abreise mit den Kindertransporten nach England gelangt war. In „Secret Survivor“ heißt es dazu: “Lila was sent to a family in Manchester who was supposed to send her to school. ‘As it turned out, I was their maid,‘ she said. ‘It wasn’t good. It was a young couple with a baby. They had me taking care of the baby, making the beds, laying the fire. I didn’t know how to do any of that. I didn’t even know how to handle money. That didn’t work out. They shoved me off to another family.‘ The next family she went to live with had two young girls, ages 9 and 11. Between the chores of scrubbing floors, doing dishes, and taking care of the house, Lila learned English from the girls while they did their homework at that time. She was able to communicate with her sister through HIAS. ‘We kept in touch, dropped a note every once in a while. She was treated well, like one of their other kids. But, eventually, Coventry was bombed, the family lost their house, and Ruth moved to Leeds.‘” Am 14. November 1940 wurden große Teile der Innenstadt von Coventry bei einem deutschen Luftangriff zerstört. Es war der schlimmste Angriff während des Zweiten Weltkriegs auf eine englische Stadt mit den meisten Todesopfern und Zerstörungen. In der kollektiven Erinnerung der Briten hatte dieser Angriff eine enorme Bedeutung. Als unmittelbare Folge musste Ruth aus der zerstörten Stadt zu einer neuen Pflegefamilie nach Leeds wechseln.

Lieselottes erfolgreiche Weiterreise nach Chicago

Ein Zweig der Familie Hochstädter aus Lampertheim war bereits Anfang des vergangenen Jahrhunderts nach Chicago ausgewandert. Dort lebte Jenny Selig (*1883), eine Cousine von Settchen Guckenheimer, zusammen mit ihrem Mann Sidney (*1873) und ihrer Mutter „Tante Sofia“ (*1854) in der Constance Avenue 7325 im Südosten von Chicago. Ihr jüngerer Bruder Rudolf Hochstädter (*1893) lebte ebenfalls dort in unmittelbarer Nachbarschaft. Settchen Guckenheimer nutzte diese verwandtschaftlichen Beziehungen und bat ihre Cousine, die Enkelkinder bei sich in der Familie in Chicago aufzunehmen. 2014 erinnerte sich Lieselotte: „My grandfather had money. He distributed it in America and in Switzerland. He sent money to a cousin in Chicago, and she arranged for me to stay with her.” Mit der finanziellen Unterstützung durch Adolf Guckenheimer war es Jenny Selig im Juni 1940 endlich gelungen, die notwendige Bürgschaft (das „Affidavit“) für Lieselotte aufzubringen und ihr das Einreisevisum in die USA zu verschaffen. Lieselotte schaffte es nach eigenen Aussagen, mit einem Minensuchboot von Liverpool nach New York zu reisen. Von dort gelangte sie mit dem Zug nach Chicago zu „Tante Jenny“ und ihrer Familie. Sie lebte sich rasch ein, begann zu arbeiten, lernte schnell Englisch und versuchte sich von der Vergangenheit zu lösen: „I just didn’t want to be reminded. I didn’t want to let it come up every day. I just sort of swept it under the carpet“, schildert sie 2014 ihre damalige Situation.

Die zahlreichen Briefe der Großeltern und ihr Ende

Mit Kriegsbeginn September 1939 kam der Postverkehr zwischen Deutschland und England praktisch zum Erliegen. Ein Austausch von Nachrichten zwischen den Großeltern und ihren Enkelkindern war nur noch über jüdische Hilfsorganisationen bzw. über das Rote Kreuz möglich. Dagegen erfolgte der Briefwechsel mit Jenny Selig und Lieselotte in Chicago auf dem regulärem Postweg. 34 Briefe nach Chicago, darunter fünf Postkarten, sind von den Großeltern Guckenheimer erhalten geblieben. Das dürfte etwa die Hälfte der Briefe sein, die sie zwischen Juni 1940 und November 1941 an Lieselotte geschickt haben. Aus der unter den Bedingungen nationalsozialistischer Zensur verfassten Korrespondenz wird ersichtlich, dass die Großeltern auch für Ruth die Überfahrt von England in die USA ermöglichen wollten. Außerdem planten sie ihre eigene Ausreise in die USA. So bittet Adolf Guckenheimer in seinem Brief vom 30. März 1941 Jenny Selig und Lieselotte um weitere Unterstützung bei der Ausreise in die USA:

„In unseren vorhergehenden Briefen haben wir ja alles ausführlich geschrieben, was heute alles verlangt wird, bis man die Bestellung nach Stuttgart [ins amerikanische Konsulat] bekommt. Aber vor allem muss man eine gute Bürgschaft besitzen, zum Beispiel l. [liebe] Jenny, Du wirst uns aufnehmen vorerst und solange sorgen, bis wir uns mit unseren Enkelinnen unseren Haushalt selbst übernehmen können. Auch l. [liebe] Lieselotte kann mitbürgen und soll sich von ihrem Chef eine Bescheinigung ausstellen lassen, dass sie 25-30 Dollar die Woche verdient. Und brauchen [wir] womöglich gar kein Akkreditiv mehr. Ist die dann für gut befunden, bekommt man seine A. C. [Akkreditiv] Bescheinigung, dann muss man sich für Schiffskarten sorgen, welche auch mit Dollar bezahlt werden. Ist dies erledigt, dann wird man vorgeladen nach St. [Stuttgart] und bekommt sein Visum. Dass dieses alles viel Mühe & Arbeit kostet, kann ich mir wohl denken. Und ist es uns sehr leid, l. [liebe] Jenny, dass wir Dich so in Anspruch nehmen müssen, aber wenn G. G. W. [der große Gott will], können wir und unsere Enkelinnen alles wieder gut machen.“

30-04-1941 Guckenheimer

Die Bemühungen der Großeltern um eine Bürgschaft, ein Einreisevisum und die Passage in die USA blieben ohne Erfolg. Im Sommer 1941 verschärften die USA ihre Einreisebestimmungen und verlangten zwei Bürgschaften für das begehrte „Affidavit“. Zudem gestaltete sich die Korrespondenz mit Jenny und Lieselotte immer schwieriger. Briefe gingen offenbar verloren, angekommene Briefe wurden erst Wochen später beantwortet. Die Großeltern waren immer verzweifelter und resignierten, als im Oktober 1941 die ersten Deportationszüge Frankfurt „nach drüben“ verlassen hatten. Settchen Guckenheimer schrieb am 23.10.1941 in einem ihrer letzten Briefe an Lieselotte und die Familie Selig in Chicago: „Vielleicht kommt auch für uns noch Hilfe, ehe es zu spät ist. Täglich gehen von hier Wagen ab nach drüben. Wir machen nichts und kann es dann kommen wie es kommt. … Morgen ist mein Geburtstag und wenn ich zurückdenke, erfüllen traurige Erinnerungen mein Gemüt“ (23-10-1941 Guckenheimer). Offensichtlich hatten die Verwandten in Chicago ihre verzweifelte Lage in Frankfurt nicht richtig eingeschätzt.

Zwei Jahre nach Kriegsende holte Lieselotte ihre Schwester Ruth aus Leeds zu sich nach Chicago. Bereits während des Krieges 1943 hatte Lieselotte ihren Nachbarn in Chicago Leland Winter (*1914) geheiratet. Ruth heiratete am 1. Februar 1948 in Chicago Siegbert Veit, den sie zuvor in Leeds kennengelernt und 1947 nach Chicago mitgebracht hatte. Schließlich holte Lieselotte 1948 auch „Oma Thekla“ (*1874) zu sich in die USA, die im Alter von 71 Jahren das Konzentrationslager Theresienstadt überlebt hatte. „Opa Ludwig“ hatte 1944 Theresienstadt nicht überlebt.

Wo sich die Großeltern Guckenheimer befanden, davon wusste nach dem Krieg niemand etwas. Zunächst wurden sie in Brasilien vermutet, später glaubte man, sie seien im Getto von Riga ums Leben gekommen. Deren Schicksal sollte sich erst in den 1970er-Jahren mit der Veröffentlichung des sog. Jäger-Berichts klären. Darin war unter dem Datum 25. November 1941 in Kaunas im Fort IX die Ermordung der „2.934 Umsiedler aus Berlin, München u. Frankfurt a. M.“ protokolliert worden.

ADDENDUM

Im Oktober 2024 besuchte ich zum zweiten Mal die Familien Veit Hutter und Winter in Chicago. Sie sind die Nachfahren der Familie Guckenheimer/Koch. Dabei traf ich noch einmal die einzig noch lebende Zeitzeugin Ruth Veit, geb. Koch, die Enkeltochter von Adolf und Settchen Guckenheimer. Ruth musste im März 1939 als 13-jährige Vollwaise ihre Großeltern in Frankfurt verlassen und konnte mit einem Kindertransport nach England flüchten. Ihre 15-jährige Schwester Lieselotte folgte einen Monat später ebenfalls mit einem Kindertransport nach England. Ruth ist inzwischen 99 Jahre alt und lebt in einem Seniorenstift in der Nähe von Chicago. Es waren bewegende Momente, ihr erneut zu begegnen und ihr von meiner Erinnerungsarbeit an die Verfolgung ihrer Familie im Nationalsozialismus zu berichten.

Mein diesjähriger Besuch in Chicago hat mir viele neue Erkenntnisse gebracht. Dazu gehören insbesondere zwei lebensgeschichtliche Interviews mit Ruth Veit und Lila Williamson aus den Jahren 2011 und 2012, von denen mir die Familie jeweils eine Kopie überlassen hat. Diese Interviews schildern sehr detailliert das Leben der Familie in Groß-Gerau, Alzey und Frankfurt in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus und sind ein berührendes Dokument der Verfolgung und Flucht:

- Interview mit Ruth Veit, geb. Koch

Chicago 2011 - Interview mit Lila Williamson, geb. Lieselotte Koch

Holocaust Museum of Southwest Florida 2012

↑ Deutsch ↓ Documents / Photos

Substitute Parents

After their mother’s suicide, Oma Settchen and Opa Adolf in Groß-Gerau took care of the grandchildren, who were just one and a half and three years old, and took them into their care. A very intimate relationship developed. In 2014, Lieselotte told a journalist in Florida about her survival story and her protected early childhood with her grandparents. In the article „Secret Survivor“8[See Shell Point Life June 2014, pages 40-41.] it becomes clear that the children felt very protected and comfortable with their grandparents in Groß-Gerau. For years, they kept in touch with their father, who remained living with his parents in Alzey. The children visited him there occasionally, as well as Oma Thekla and Opa Ludwig. Thus, the Koch grandparents also remained important reference persons for the children for many years. Their importance for the children’s upbringing was emphasized by the great-granddaughter Debra Hutter, née Veit (born 1954), during my visit to the family in Chicago in February 2023. The father, on the other hand, was „not helpful“ for the children, she said. In Groß-Gerau, the Guckenheimer grandparents always had „nannies“ who lovingly cared for the children. „They lived a safe and comfortable life“, it is stated in „Secret Survivor“, until the time when the grandparents had to leave Groß-Gerau and flee to Frankfurt.

Escape to Frankfurt

At the beginning of the National Socialist boycott of Jewish businesses on the 1st of April 1933, the family had been attacked and assaulted by SA members, the grandmother was injured. Adolf and Settchen Guckenheimer were forced to give up their existence in Groß-Gerau and moved to Frankfurt with their granddaughters. The forced departure from Groß-Gerau due to persecution took place in September 1933. After Hitler’s seizure of power, the Jewish children were increasingly exposed to anti-Semitic hostility and threats at school. They were largely banned from schools, parks, swimming pools and sports clubs, from public theaters and fairs. The move to Frankfurt, a city with a strong Jewish community, may therefore also have been intended to better protect the children.

Philanthropin and Dr. Heinemann’s boarding school for girls

In Frankfurt, the granddaughters initially attended the Philanthropin, a Jewish school located in the immediate neighborhood of the grandparents‘ new rented apartment at Scheffelstraße 25 in Frankfurt’s Nordend. By 1935, the children had moved to the „Dr. Heinemann’sche Mädchenpensionat“ at 84 Mendelssohnstrasse in Frankfurt’s Westend, which was intended to prepare its students for emigration to Palestine.9Ruth Veit gave these details about the school visits when she visited Frankfurt in 2006. She had participated with her husband in the visit program of the city of Frankfurt. This was reported to me by Angelika Rieber, who has been in charge of the visiting program for former Jewish residents of the city since 1990. The boarding school was run as a boarding and external school and was a Jewish private college with „officially approved instruction“ up to the „Obersekunda“ (class 11). Whether the children lived in the boarding school or with their grandparents during this time is something Ruth Veit can no longer remember today. In 1936, her grandparents had moved to Hammanstraße 4 into a new rented apartment with six rooms, including a children’s bedroom with „2 beds, 1 wardrobe, 1 chest of drawers, 1 electric sewing machine, 2 armchairs, 2 bed rugs.“10So says a memorial record of Ruth from 1957 (HHStAW Bestand 519/A Nr. FFM 6815/1, p. 7). The distance from the new apartment to the school was about 1.5 kilometers, which made it convenient for the children to walk. In this regard, there was also the very practical possibility that the children would continue to sleep with their grandparents and use the boarding school as an externat.

November Pogroms 1938

Lieselotte recalled the traumatic experience of the „Reichskristallnacht“. That night, Otto Koch, the children’s father, had been imprisoned in Alzey and, like 30,000 other Jewish men, was deported to the concentration camp in Buchwald. At the age of 41, he died there a few weeks later on 8th December 1938. Her memories mix the „Reichskristallnacht“ with the SA attack on her grandparents in their residence in Groß-Gerau, which had already taken place in 1933 and had led to the family’s move to Frankfurt. At that time, the grandmother had suffered injuries and the family had to seek shelter in the windowless bathroom of the apartment.11After so many years, Lila (Lieselotte) Williamson’s memoirs were not always very precise in the time and place information. For example, she relocates the family’s flight from Gross-Gerau to Frankfurt to the time after the November pogroms in 1938, although the grandparents had already fled to Frankfurt in 1933. The two dramatic events are five years apart.

”Kindertransporte”

After the devastating November pogroms, the world public was alarmed about the situation of the Jews in Germany, but only the British government decided to act quickly and agreed with a delegation of British Jews and Quakers on the admission of an unlimited number of children and adolescents threatened in the German Reich, who were allowed to immigrate without bureaucracy up to the age of 17 with immediate effect. Their parents, however, had to remain in Germany. Direct negotiations between the legendary Geertruida Wijsmuller12Geertruida Wijsmuller was an influential Dutch Jewess and banker’s wife who collaborated with Recha Freier from Berlin, the founder of the „Children’s and Youth Aliyah,“ an organization that from 1933 attempted to bring as many Jewish children as possible to safety in Palestine. and Adolf Eichmann in Vienna, who at the time headed the „Central Office for Jewish Emigration“, had ensured the Nazi regime’s general toleration of the privately organized transports to England. The condition for the departure was that the children were only allowed to carry one suitcase and no more than 10 Reichsmark and that the parents did not accompany them to the train platform. The public should not notice anything of the dramatic farewell scenes.

In Frankfurt, starting in January 1939, the children’s emigration was organized by the Jewish welfare organization of the Jewish community for all of southwestern Germany. The children on the trains were accompanied by a few adults from the welfare organizations until they reached the last stop before the Dutch border in Bad Bentheim. After harassing checks of the children and their luggage by the Gestapo, the train continued to Hoeck van Holland, from where a ferry took the children across the English Channel to Harwich. From there, they were first taken to reception camps until a suitable foster family could be found for them.

The first Kindertransport to England departed from Berlin on 1st December 1938, bringing 196 Jewish children to London. The beginning of World War II on 1st September 1939 marked the official end of Kindertransports from Germany. By this time, over 10,000 children had managed to escape from Germany to England.

Ruth and Lieselotte’s rescue from the Nazis

Adolf and Settchen Guckenheimer had understood the hopeless situation for Jews in Germany at an early stage and made continuous efforts to emigrate. Through the initiative of the Kindertransporte, the departure of their granddaughters was now suddenly possible. Since both children had become orphans through the recent death of their father, they had a good chance of receiving one of the sought-after places for the Kindertransporte. Orphans, especially if they were young girls, were given first consideration by the Jewish aid organizations. They also found it easier to find a place in a foster or adoptive family in England. The article „Secret Survivor“ describes the separate departure of the two grandchildren, without giving more precise time details: “From Frankfort, the family managed to get Lila and Ruth transported to England with Kindertransport through a rescue organization known as HIAS. ’They tried to get the children out of Germany as fast as possible to keep us out of concentration camps,’ recalled Lila. Her sister went first, and was young enough to be adopted by a family in Coventry.”

Ruth came to England in March 1939 ahead of her older sister on a Kindertransport, she recalled during her visit to Frankfurt in 2006. In Coventry, she had been well received by a family. Two letters from her grandparents to her in Coventry, which have been preserved, speak of the new adoptive parents as „Uncle and Aunt Josef,“ to whom Ruth is apparently „a good support“ and in whose business she can „show herself useful.“ In her letter of March 28, 1940, the grandmother encourages her not to hang her head: „The time will come when we can all be together again. … Be lively and cheerful and there are so many Frankfurt girls there and you can exchange your thoughts with each other!“

Lieselotte had fared less well, arriving in England with the Kindertransports some months after Ruth’s departure. In „Secret Survivor“ it reads in this matter: “Lila was sent to a family in Manchester who was supposed to send her to school. ‘As it turned out, I was their maid,‘ she said. ‘It wasn’t good. It was a young couple with a baby. They had me taking care of the baby, making the beds, laying the fire. I didn’t know how to do any of that. I didn’t even know how to handle money. That didn’t work out. They shoved me off to another family.‘ The next family she went to live with had two young girls, ages 9 and 11. Between the chores of scrubbing floors, doing dishes, and taking care of the house, Lila learned English from the girls while they did their homework at that time. She was able to communicate with her sister through HIAS. ‘We kept in touch, dropped a note every once in a while. She was treated well, like one of their other kids. But, eventually, Coventry was bombed, the family lost their house, and Ruth moved to Leeds.‘” On 14th November 1940, large parts of Coventry city center were destroyed in a German air raid. It was the worst attack during World War II on an English city with the most deaths and destruction. In the collective memory of the British, this attack had enormous significance. As a direct consequence, Ruth had to move from the destroyed city to a new foster family in Leeds.

Lieselotte’s successful onward journey to Chicago

A branch of the Hochstädter family from Lampertheim had expatriated to Chicago at the beginning of the last century. There Jenny Selig (*1883), a cousin of Settchen Guckenheimer, lived with her husband Sidney (*1873) and her mother „Aunt Sofia“ (*1854) at 7325 Constance Avenue in southeast Chicago. Her younger brother Rudolf Hochstädter (*1893) also lived there in the immediate neighborhood. Settchen Guckenheimer took advantage of these family ties and asked her cousin to host the grandchildren in her family home in Chicago. In 2014, Lieselotte recalled: „My grandfather had money. He distributed it in America and in Switzerland. He sent money to a cousin in Chicago, and she arranged for me to stay with her.“ With the financial support of Adolf Guckenheimer, Jenny Selig finally succeeded in June 1940 in raising the necessary guarantee (the „affidavit“) for Lieselotte and getting her an entry visa to the United States. According to her own statements, Lieselotte managed to travel from Liverpool to New York on a minesweeper. From there she took the train to Chicago to join „Aunt Jenny“ and her family. She soon settled in, began to work, quickly learned English and tried to detach herself from the past: „I just didn’t want to be reminded. I didn’t want to let it come up every day. I just sort of swept it under the carpet,“ she says in 2014, describing her situation at the time.

The numerous letters of the grandparents and their end

With the beginning of the war in September 1939, postal traffic between Germany and England came to a complete standstill. After that, an exchange of messages between the grandparents and their grandchildren was only possible via Jewish aid organizations or via the Red Cross. In contrast, correspondence with Jenny Selig and Lieselotte in Chicago could take place by regular mail. 34 letters to Chicago, including five postcards, have been preserved from the Guckenheimer grandparents. This is probably about half of the letters they sent to Lieselotte between June 1940 and November 1941. From the correspondence written under the conditions of National Socialist censorship it is evident that the grandparents also wanted to make passage from England to the United States possible for Ruth. In addition, they were planning their own departure to the USA. Thus, in his letter of 30th March 1941, Adolf Guckenheimer asks Jenny Selig and Lieselotte for further support for their emigration to the USA:

„In our previous letters we have written in detail about everything that is required today until you get the order to Stuttgart [to the American Consulate]. But above all, one must have a good guarantee, for example dear Jenny, you will take us in for the time being and provide for us until we can take over our household ourselves with our granddaughters. Also dear Lieselotte can be a guarantor and should get a certificate from her boss that she earns 25-30 dollars a week. And we may not even need a letter of credit anymore. If that is then found to be good, you get your A. C. [letter of credit] certificate, then you have to arrange for ship tickets, which are also paid with dollars. Once this is done, you are invited to St. [Stuttgart] and get your visa. That this all costs a lot of effort & work, I can well imagine. And we are very sorry, dear Jenny, that we have to make such demands on you, but if the great God wills, we and our granddaughters can compensate for everything.“

30-04-1941 Guckenheimer

The grandparents‘ efforts to obtain an Affidavit, an entry visa, and passage to the U.S. were without success. In the summer of 1941, the U.S. tightened its immigration regulations and required two guarantees for the sought-after „Affidavit“. In addition, correspondence with Jenny and Lieselotte became increasingly difficult. Letters were apparently lost, letters that arrived were not answered until weeks later. The grandparents were increasingly desperate and resigned in October 1941 when the first deportation trains left Frankfurt „for over there„. On 23rd of October 1941, Settchen Guckenheimer wrote in one of her last letters to Lieselotte and the Selig family in Chicago: „Maybe help will come for us, before it is too late. Wagons leave here daily for over there. We do nothing and then it can come as it comes. … Tomorrow is my birthday and when I think back, sad memories fill my mind“ (23-10-1941 Guckenheimer). Obviously, the relatives in Chicago had not properly considered their desperate situation in Frankfurt.

Two years after the end of the war, Lieselotte brought her sister Ruth from Leeds to live with her in Chicago. Already during the war in 1943, Lieselotte had married her neighbor in Chicago, Leland Winter (*1914). Ruth married Siegbert Veit (*1923) in Chicago on 1st February 1948, whom she knew before in Leeds and had brought with her to Chicago in 1947. Finally, in 1948, Lieselotte also brought “ Oma Thekla“ (*1874) to join her in the USA, who had overcome the Theresienstadt concentration camp at the age of 71. “ Opa Ludwig“ had died in Theresienstadt in 1944.

No one knew where the Guckenheimer grandparents were after the war. At first they were assumed to be in Brazil, later it was believed that they had perished in the Riga ghetto. Their fate was finally clarified in the 1970s with the publication of the so-called Jäger Report. In this report, the murder of „2,934 resettlers from Berlin, Munich and Frankfurt a. M.“ was recorded in Kaunas in Fort IX on November 25, 1941.

ADDENDUM

In October 2024, I visited the Veit Hutter and Winter families in Chicago for the second time. They are the descendants of the Guckenheimer/Koch family. I met the only surviving contemporary witness Ruth Veit, née Koch, the granddaughter of Adolf and Settchen Guckenheimer. Ruth had to leave her grandparents in Frankfurt in March 1939 as a 13-year-old orphan and was able to flee to England on a Kindertransport. Her 15-year-old sister Lieselotte followed a month later, also on a Kindertransport to England. Ruth is now 99 years old and lives in a retirement home near Chicago. It was moving to meet her again and to tell her about my work remembering the persecution of her family during the Nazi era.

My visit to Chicago this year brought me many new insights. These include, in particular, two biographical interviews with Ruth Veit and Lila Williamson from 2011 and 2012, which the family gave me a copy of. These interviews describe the family’s life in Groß-Gerau, Alzey and Frankfurt during the National Socialist era in great detail and are touching testimonies of persecution and flight:

- Interview with Ruth Veit, née Koch

Chicago 2011 - Interview with Lila Williamson, née Lieselotte Koch

Holocaust Museum of Southwest Florida 2012

Dokumente / Documents ↑ Anfang / Top

Jg. 35 (21.12.1933) H. 51, S. 8

Jg. 39 (16.9.1937) H. 37, S. 10

→ See Secret Surviver

→ See Secret Surviver

Anmerkungen / Notes

- 1Foto (1939) aus dem Privatbesitz der Familie Veit / private property of the Veit family.

- 2Foto (1939) aus dem Privatbesitz der Familie Veit / private property of the Veit family.

- 3Siehe Shell Point Life June 2014, Seite 40-41.

- 4Diese Angaben zu den Schulbesuchen machte Ruth Veit 2006 bei ihrem Besuch in Frankfurt. Sie hatte mit ihrem Mann gemeinsam am Besuchsprogramm der Stadt Frankfurt teilgenommen. So berichtete mir Angelika Rieber, die das Besuchsprogramm für ehemalige jüdische Bewohner der Stadt seit 1980 leitet.

- 5So heißt es in einem Gedächtnisprotokoll von Ruth aus dem Jahre 1957 (HHStAW Bestand 519/A Nr. FFM 6815/1, S. 7).

- 6Lila (Lieselotte) Williamsons Erinnerungen waren nach so vielen Jahren nicht immer sehr präzise in den Zeit- und Ortsangaben. So verlegt sie die Flucht der Familie von Groß-Gerau nach Frankfurt in die Zeit nach den Novemberpogromen 1938, dabei waren die Großeltern bereits 1933 nach Frankfurt geflüchtet. Die beiden dramatische Ereignisse liegen fünf Jahre auseinander.

- 7Geertruida Wijsmuller war eine einflussreichen holländischen Jüdin und Bankiersfrau, die mit der Berlinerin Recha Freier zusammenarbeitete, der Gründerin der „Kinder- und Jugend-Alija“, einer Organisation, die ab 1933 versuchte, möglichst viele jüdische Kinder nach Palästina in Sicherheit zu bringen.

- 8[See Shell Point Life June 2014, pages 40-41.]

- 9Ruth Veit gave these details about the school visits when she visited Frankfurt in 2006. She had participated with her husband in the visit program of the city of Frankfurt. This was reported to me by Angelika Rieber, who has been in charge of the visiting program for former Jewish residents of the city since 1990.

- 10So says a memorial record of Ruth from 1957 (HHStAW Bestand 519/A Nr. FFM 6815/1, p. 7).

- 11After so many years, Lila (Lieselotte) Williamson’s memoirs were not always very precise in the time and place information. For example, she relocates the family’s flight from Gross-Gerau to Frankfurt to the time after the November pogroms in 1938, although the grandparents had already fled to Frankfurt in 1933. The two dramatic events are five years apart.

- 12Geertruida Wijsmuller was an influential Dutch Jewess and banker’s wife who collaborated with Recha Freier from Berlin, the founder of the „Children’s and Youth Aliyah,“ an organization that from 1933 attempted to bring as many Jewish children as possible to safety in Palestine.

- 13Foto aus dem Privatbesitz der Familie Veit / Private property of the Veit family.

- 14Foto aus dem Privatbesitz der Familie Veit / Private property of the Veit family.

- 15Foto aus dem Privatbesitz der Familie Veit / Private property of the Veit family.

- 16Foto aus dem Privatbesitz der Familie Veit / Private property of the Veit family.

- 17Foto aus dem Privatbesitz der Familie Veit / Private property of the Veit family.

- 18Foto 2023, Hermann Tertilt.

- 19Foto Hermann Tertilt.

- 20HHStAW Bestand 519/A Nr. FFM 6815/1, S. 7

- 21Foto Hermann Tertilt.

- 22Foto aus dem Privatbesitz der Familie Veit / Private property of the Veit family.